Film

Film adaptations, updates, and interviews.

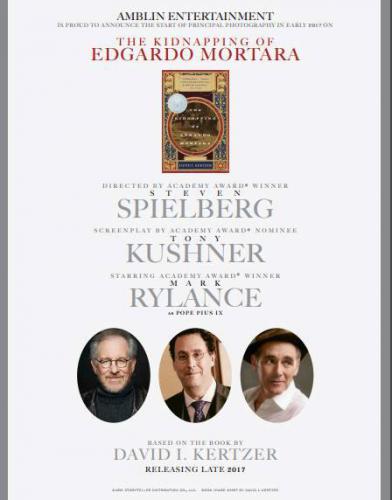

In 2016 Steven Spielberg announced his intention to make a film based on David Kertzer’s book, The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, with a screenplay by Tony Kushner. Initially planned to be shot the following year, the project, after much development, including a complete screenplay by Kushner, has been delayed. As soon as further news is available on the film project, it will be available here.

Efforts are also underway to produce a series of documentaries based on two of Kertzer’s more recent books: The Pope and Mussolini and The Pope at War. When more information is available, it too will be available here.